I don’t usually do these year in review posts, but this year I’m going to, and it’s because it’s been, well A YEAR. I suspect this is a year I’m going to want to look back and have some kind of record of, because living through history, while thoroughly miserable at the time, is something we’re all curious about in retrospect. Also, because as I was reflecting about 2020 to myself, I had to admit that, while it was clearly a mire of suck that we all had to trudge through that feels like it has gone on FAR too long, for me it was also a really, all around, pretty good year. But also a year I can sum up in one sentence: that was a lot harder than I thought it would be.

Here are the highlights.

Professionally, I had a really phenomenal year. It didn’t feel that way going through it, because, well, every single thing I worked on this year turned out to be a lot harder than I thought it would be. But it doesn’t change that, at the end of the year, I am in a far, far better place than I was last December.

Last year in January my business partner Megan and I sat down and had a reckoning about how our business model was not working. We’d been publishing our flagship series for about eight months at that point using a free first in series model, and we just weren’t seeing the read through we needed to justify our ad spend. We weren’t making a profit, and none of the tools I had available were going to make us make a profit. We needed to switch up our model and try something entirely different.

Folks, when you have eight books out, making a pivot like that is not easy. It required us to add books to our schedule, rearrange everything, change all the backlinks, redo our ad strategy…everything. We spent months doing it. But our new strategy (Kindle Unlimited with a free magnet book that is related to, but not in, each series) is now making us a profit. We paid ourselves for the first time in 2020. Sales fluctuate, but we are continuing to turn a profit now, even in the low months. We still have a little ways to go before we will have paid back our investment, but we’ve found a model that works. Last year around this time, I was facing a massive failure (we spent a lot of money proving that model didn’t work) and unsure if there was anything I could do that would work. This year, I’m staring down the daunting task of learning to scale. BUT WE HAVE SOMETHING TO SCALE! I cannot even tell you how exciting that is. It has taken me years and years and years to get to this point, and I’m excited about it, even if it means 2021 is going to be a whole lot of work.

Megan and I (and our friend Lauren) also launched our epic fantasy series this year. We put out six books in four months over the summer (including two in our rom com series), and had a week-to-week schedule that was (apparently) doable, but also a little soul-crushing. I knew epic fantasies were harder to write than romances, but we already had them written. What I did not expect was how much harder the production on them would be. I knew they were *longer,* but they are only twice as long as our romances, and yet still managed to be about five times the amount of work. The continuity was a big part of that. There’s a lot to keep track of in a world that big, and we spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to make sure all the right things are capitalized, all the distances were calculated correctly, and how to get our characters across that river we forgot was there until we got to the galley stage and weren’t going to rewrite the chapter now. It was, as they say, a hell of a lot harder than I thought it was going to be. But we did it! And those books started profiting (modestly) right out of the gate. Megan and Lauren had been working on those books for decades, and I’ve been on board for about six years. Having them finally published (and doing well!) is a triumph.

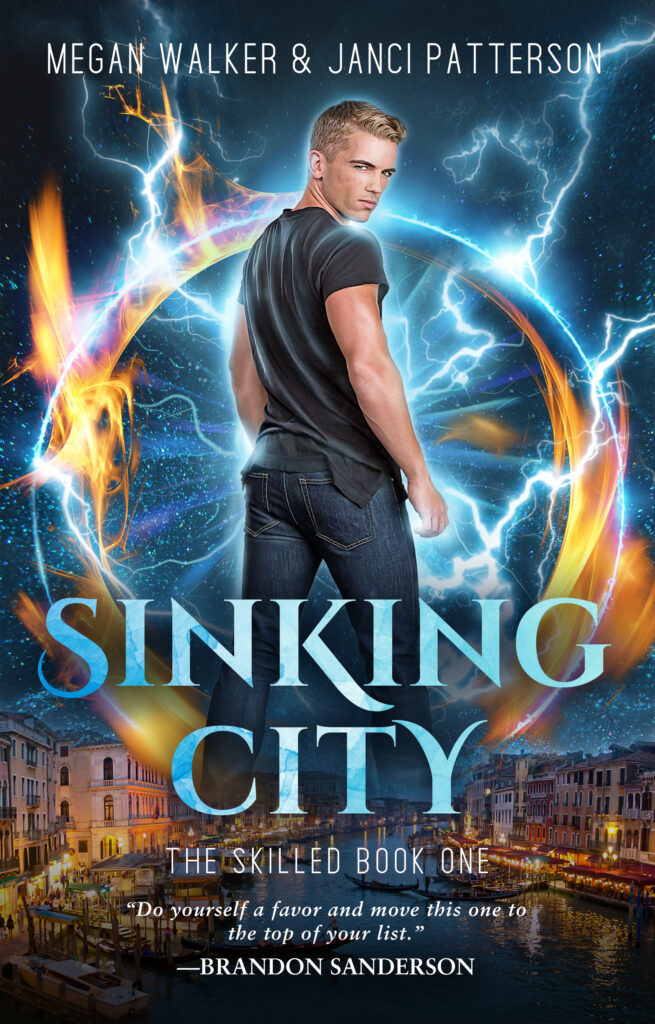

Because we are crazy, Megan and I ALSO thought it would be a good idea to launch our paranormal romance series this year. We were hoping to ride a wave that might follow Midnight Sun. If that wave exists, we did not catch it, but that’s the danger of chasing trends, I suppose. We put out Sinking City, a book Megan wrote and I revised and I’m really, fantastically proud of. We then started work on the sequel in November and, well, friends, it’s been a lot harder than I thought it would be. It’s single-handedly managed to be the hardest thing either Megan or I have ever written, and we’ve written some really hard books. It’s kicking both our asses on a regular basis. We’ve been working on the outline for months, have produced a lot of words that won’t be in the book, and some that I dearly hope will, because this book has a deadline. We won’t release it unless it’s good. I’m not worried about that. But what it’s going to do to us over the next few months trying to make it good is its own question.

I quit ghostwriting back in the spring, partly because I was pretty burned out, and partly because I couldn’t do that and launch all this other stuff and I thought taking a gamble on myself was worth the risk. I put all the time I would have put into ghost writing into my personal projects. I thought when I quit I had maybe four months before I would have to go back to it. Eight months later not only have I managed to stretch this far, but I’ve also secured income which means I have another whole YEAR to get my stuff going (barring personal financial catastrophe) so that I don’t have to go back to writing other people’s stuff. That’s something I didn’t think I could do, but I did, and I’m thrilled about it.

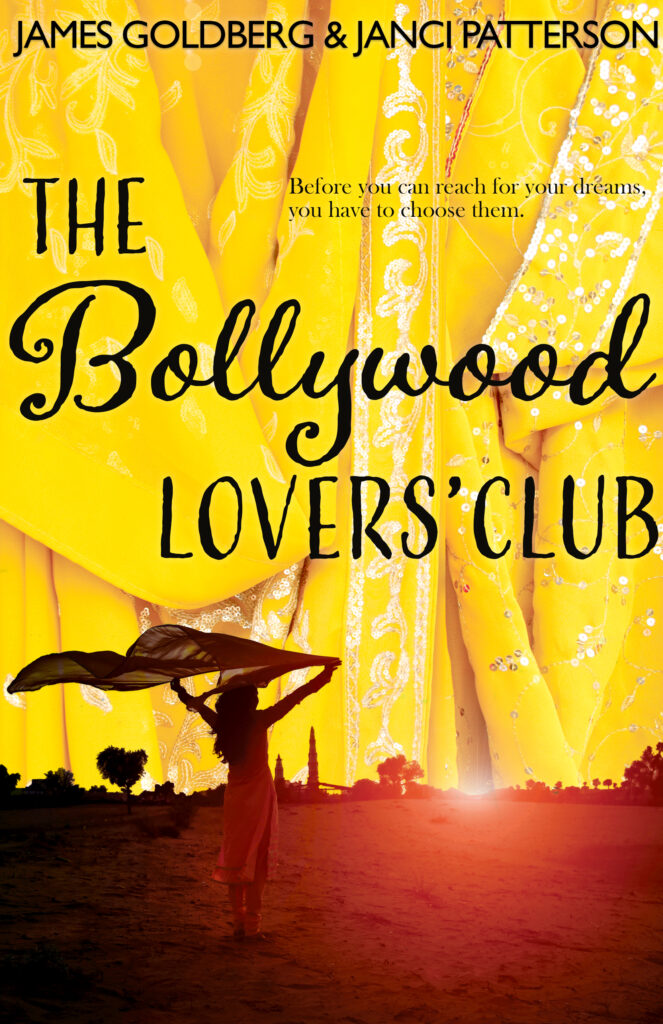

BUT that doesn’t mean I’m not writing in other people’s worlds. I had some real motion on some of my not-with-Megan co-writing projects this year. James Goldberg and I are gearing up to finally release our YA Bollywood novel, which we’ve been working on for a long, long time. I am so excited to finally share that book with the world. I’m really proud of what we accomplished.

A couple years ago I was offered the opportunity to co-write the last book in Brandon Sanderson’s Alcatraz vs. the Evil Librarians series. Brandon had written the first few chapters and run into some road blocks, and he wanted me to take his notes and his beginning and rework it and then finish it. I was super excited about it—I’ve been a huge fan of the series since before the first book came out (on which I was a beta-reader). I love the characters, the world, everything. I took Brandon’s chapters and notes, re-read the series to make more notes, and then wrote the first half in about a week, then took a break of a few months and wrote the second half in another week. I got some notes back a long while later and did another draft on it in another week. (This is an Alcatraz tradition. If I remember correctly, Brandon wrote the first draft of the first book in about ten days.) The thing was a joy to work on start to finish, and remains to this day the most purely fun thing I have ever written. The news this year is that the book is FINALLY under contract with a publisher, and has a tentative release date. (Spring, 2022–now delayed until Fall 2022.) Finally having something to tell people when they ask when that book is coming out feels pretty damn good. I’m so thrilled to have been part of the series, and having a release date makes the whole thing feel a lot more real. There have been times over the last few years when I wondered if writing that book really happened. But it did! And next year, you will get to read it.

The other really exciting news is that this year I was offered three tie-in “novellas” to write in Brandon’s Skyward world. The books are directly related to the original series and follow all the side characters while the main character (Spensa) is away from them for all of book three. The books interact with the main series in some really interesting ways, which makes them both exciting and challenging to write. I wanted to have more time to write them, but contracts, folks, turn out that they’re a lot harder than I thought they would be, and I’m just now getting started writing book one. (These are supposed to be done in July. We Shall See.) I knew these were going to be harder to write than Alcatraz, for many reasons, but friends, they are a lot harder to write than I thought they would be. Mostly, I think, because I psych myself out too much about living up to the original series. What I need to do is let myself write first drafts that are bad and then fix them. And what I’ve written so far is real bad, so that’s a triumph of its own I suppose! I’m better at fixing bad writing than I am at writing good stuff to begin with, so that’s to be expected. It will be good before I turn it in, and if it isn’t, then I’ll get feedback and THEN make it better, long before it’s published. These books will not see the light of day until both Brandon and I are satisfied with them. But it’s downright terrifying, and also beyond exciting, and dealing with that maelstrom has been a hurricane and a half. It’s a real good problem to have, though, and I’m excited to keep having it over the next six months. (I really still think I can get it done in six months, but I’m also still grappling with the catastrophe that is the Sinking City sequels at the same time. So.)

I think that’s about it professionally. So on to personally. And, oh yeah…

There was a pandemic this year, that has pretty much turned everyone’s lives upside down. On the surface, this has affected me far less than most people. My kids already did online school. (Third grade and preschool this year, through K12 and Upstart.) My husband and I already work from home. We are used to all being on top of each other all the time. BUT we are also used to having social support systems that became next to non-existent. I had to quit my weekly writing group which I had continued, uninterrupted, since 2005. We indefinitely paused our weekly roleplaying group, which had been meeting, uninterrupted, since 2005. Both of those things, it turned out, were really good for my mental health, and not having them is . . . not. My kids haven’t seen their friends in months, and it will be more months yet before we get to be vaccinated and the world can begin the slow slant toward normal again. We will get there. But when the world shut down in March, we hoped we would be there by July.

It’s possible we were right, we just were thinking of the wrong July.

There have been some really horrifically low moments, like the day I had to tell my kids they couldn’t play with their friends anymore (which I cried about and likened to being on Survivor and every week voting someone else you love off your island.) We lost my mother-in-law in April when the shut down was tightest, and couldn’t even really have a funeral. (Her passing was not COVID-related, but the timing made it much more difficult to grieve. I miss her, and I probably always will.) There was the moment back around May when my daughter earnestly asked me if things would ever go back to normal, and I sat down and explained to her what a vaccine was, and why the world probably wouldn’t go back to normal until we had one, and exactly how long that was likely to take.

But, through all of it, there have been some bright moments, too. After that conversation, my children both started asking in their prayers for a vaccine. They prayed and prayed and prayed for it, and you should have seen the light in their eyes when I told them that not only had a vaccine been developed faster than ever in the history of mankind, but that it was much more effective than anyone would have guessed it would be. My kids, on the whole, have been incredibly adaptable and mature about the whole thing, and while I still hear some whining about when we’re going to be able to go to the pool again, or other such things, they do a whole lot less whining about the whole thing than I do. When the George Floyd protests happened this summer we also had a lot of conversations about prejudice that were really good to have, and I extended those conversations outside my own house to friends and acquaintances, and with only a couple of exceptions those conversations were good and meaningful and productive. I wish there weren’t horrible things happening in the world that necessitate those conversations, but since there are, I’ve been grateful for the opportunity to talk about them. A harassment scandal I was involved in also got kicked up again this year, and while I did not enjoy having to deal with that whole host of emotions again, I was able to engage with it in different ways than I did last time, and that was good for me, even if it wasn’t fun.

The pandemic and its general mismanagement by governments at many levels has been horrific, and in no way am I glad it happened. But I definitely know a lot more about epidemiology than I did in January 2020, and that’s been really interesting to learn, even if I wish it was under purely academic circumstances. I have nothing good to say at all about the election of 2020, which was horrific on all levels, except that I am very, very glad that Donald Trump will no longer be president of the United States, and that is thankfully happening very soon.

Overall, the loss of my usual life patterns have forced me to find different ways of connecting. Last January I built a Little Free Library and installed it in front of my house. I was grateful for the timing when the public libraries closed in March. It’s been a wonderful way for me to feel like I’m still a part of my community without ever actually contacting anyone. In August I was offered the opportunity to take over as admin of my local Buy Nothing group, and that, too, has given me a way to serve my community without ever having to leave my house, and has been incredibly rewarding.

I bought a fire pit when the weather started turning cold, so that I could see some people on occasion and still be outside where risk of COVID transmission is lower. I was a girl scout for twelve years, but it had been decades since I’d built a fire. It’s been so fun to teach my children fire skills, and let them roast marshmallows, and sit with friends and talk in a safer way. I never would have done that if it wasn’t for the pandemic.

I’m an outing mom. I’m not great at playing on the floor, but I am great at taking my kids places and having adventures. When everything shut down, I stared in horror at a life cooped up in the house with my kids, and I knew I had to make some changes. We usually use the heck out of our museum passes, but with all that closed, I did some research and took my kids hiking for the first time. Turns out we love it. It was such a respite over the summer and in the fall to get out into the mountains where we could both avoid people and explore. We discovered some great places, our favorite of which was Dripping Rock in Spanish Fork. We’ll definitely keep doing that even once we can get back to the swimming pool and our museum passes, but I don’t know that I ever would have gotten over the hurdles of figuring out where to go without the desperation caused by the lockdowns.

Our holidays are usually pretty limited—we’re kind of holiday hermits and do our little, tiny celebrations with our little, tiny group of people. We had to be even more limited this year, which was sad, but ours weren’t impacted as much as some people’s. On Halloween, though, we decided not to trick-or-treat, mostly because at the time Utah’s mask compliance was not at a level we were comfortable with. Instead, I made a scavenger hunt for the kids (which is on the list of things that are Mom-extra that I would never do in a regular year), and my kids loved it. They didn’t really miss trick-or-treating. It was my personal favorite Halloween ever. (I told my kids we could do this instead every year and my daughter, clever as she is, announced that we should do BOTH! So I may be paying for my ingenuity next year in added work for myself, but the memory was worth it.

As winter set in, I started losing my mind a little. We couldn’t really go hiking anymore (though I have seriously thought about acquiring snow-shoes, I have not yet braved my anxieties about figuring THAT out) and the walls were closing in. I was having a hard time working (not helped by the stressful nature of the work in question, as I’ve been trying to nail down the plots of not one but TWO YA fantasy-action series), and generally sliding into depression, something I hadn’t felt in MANY years. I’m used to losing my mind a little after I have a baby, but general winter depression was different. I remarked to a friend that it felt like we were all squirrels who arrived at the winter with empty trees. This year, friends, was obviously harder than we thought it would be. My reserves were gone.

As fate would have it, that was also around the time that my friend Brandon released book four in his Stormlight Archive. Folks, I love those books. When book three came out I was knee deep in prep to put out both The Extra Series and the Five Lands Saga, and I just couldn’t commit to a book that big. I was sad about it then, and extra sad that yet ANOTHER book was coming out and I couldn’t read it. It had been long enough that I needed to start back at the beginning of the series, and that is a LOT of words that I didn’t have time for.

I was tired of being sad about things, so I decided I was going to read the books one chapter a day. It will probably take me more than a year. I’ve been at it for months and I haven’t finished book one yet, though I am getting close. It has been SO FUN to reread The Way of Kings. I’m catching all kinds of things on this read that I didn’t catch on the first time through, before I knew generally where the series was going. I’ve been discussing with my husband as I read, because he remembers much better than I do, but there are all kinds of discoveries I’m making that he had also forgotten. It’s a little spark in the dreary winter, and I’m so incredibly grateful for it.

It wasn’t quite enough to shake me out of my funk, and nothing gets me excited like a project. I was a couple weeks into my read-through when I desperately wanted to make dolls of the characters. Megan and I have dolls for all our characters, and we pre-write by roleplaying with them. We have way too much fun, but I’d also always admired the doll designers who make one-of-a-kinds that aren’t supposed to be played with, which is a whole other skill set. This would require more time and money than I had to devote to such a thing, but it quickly became apparent that if I didn’t do something to engage my creative brain, it was going to be a very terrible winter indeed, so I found the resources anyway. Making those dolls presents a challenge that keeps my brain always going, and it’s been enormously helpful in relieving the depression, which is now almost entirely gone. I’ve made four dolls with two more almost finished and another six acquired and waiting in my queue, and even more ideas after that. It’s huge and ambitious and not exactly what I would have prescribed for myself in the middle of huge ambitious writing projects and a world-wide pandemic, but I’ll take the medicine where I can find it, I suppose.